Embark on a compelling journey through DuPage County as this blog unravels the hidden chapters of the Underground Railroad against the backdrop of Black History Month. Delve into the untold stories of courage and resilience as we explore the local connections and safe havens within DuPage County that played a pivotal role in aiding fugitive slaves to freedom.

Blanchard Hall

On the campus of Wheaton College lies Blanchard Hall, named after former president Jonathan Blanchard and his son Charles Blanchard, the second president. When the college was founded in 1860, it was an abolitionist community; Jonathan and his wife May were part of that community, as well as Jonathan’s predecessor John Cross. During the Civil War, Blanchard Hall was a stop on the Underground Railroad, harboring fugitive slaves on their way to freedom as they made their way onward to Canada. It was noted that "runaway slaves were perfectly safe in the College building, even when no attempt was made to conceal their presence.”

Today, Blanchard Hall features exhibits in its lobby about freedom seekers and African American history.

Blodgett House

One of the oldest homes in Downers Grove, the house was built by Israel Blodgett and his wife, Avis. Both were outspoken abolitionists and their home has cultural significance as a stopover point on the Underground Railroad, included in the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

The Downers Grove Heritage Preservation Corporation was founded in 2007 with a mission to save and restore this historic house and create a museum focusing on the underground railroad. When the house was recently under renovation, workers found abolitionist newspapers stuffed into the walls, offering some proof of the Blodgett’s assisted freedom seekers.

Today, the Blodgett house is now a cultural center focusing on the Blodgett family and their involvement in the nationally significant Underground Railroad.

Graue Mill and Museum

While this 170-year-old flour-producing mill remains one of the few of its kind still in operation, its rumored history as a “station” on the Underground Railroad also left a lasting impression. Frederick Graue, a German immigrant, was against slavery and would hide freedom seekers in the mill’s basement as they rested on their journey to Canada. It was rumored to have a tunnel between a busy inn and the mill to facilitate the movement of those escaping slavery. Graue Mill's location on Salt Creek made it an especially ideal spot for a stop, since often passage required walking adjacent to swimming or boating through water.

Today, visitors can stop in the museum which has photographs, documents and interactive displays that tell the property’s “station” history.

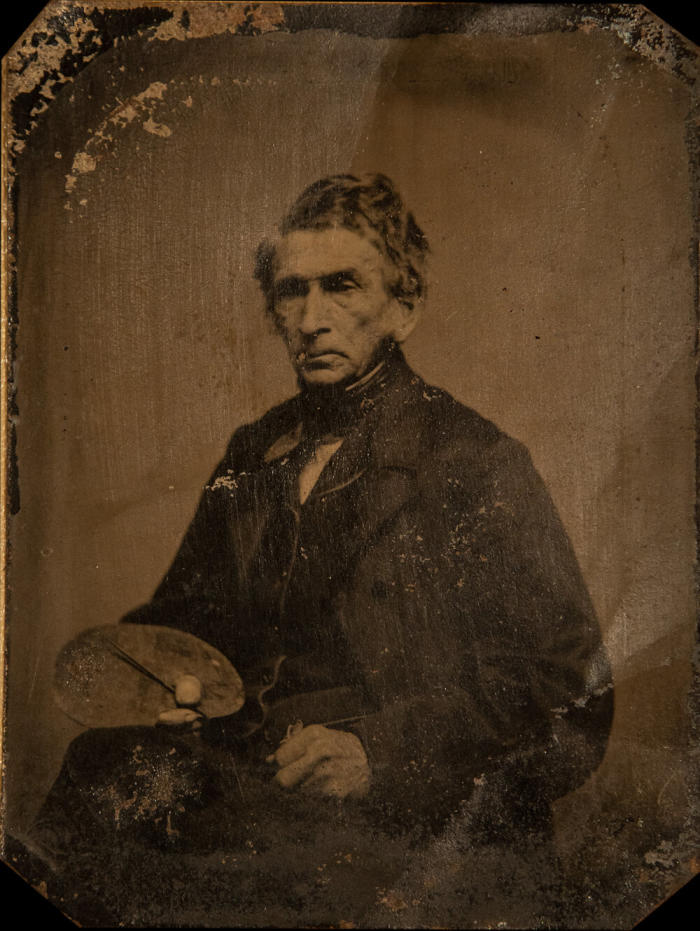

Sheldon Peck

Sheldon Peck was a resident of Lombard. He was a self-taught folk artist and gained recognition for his portraits, primarily of residents, which captured the faces and personalities of the people he painted.

In addition to his artistic pursuits, Peck was a staunch abolitionist who actively participated in the Underground Railroad. His home in Lombard is believed to have served as a safe house for escaped slaves seeking refuge. According to the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, Peck’s youngest son Frank kept a diary in which he recalls seven escaped slaves living with his family.

Today, his portraits and the history of his involvement in the Underground Railroad contribute to a broader understanding of the complex and interconnected issues of art, activism, and social justice in 19th century America. Reproductions of his paintings are currently located at the Sheldon Peck Homestead, now owned and operated by the Lombard Historical Society.